Weight Loss Research

Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity

John P.H. Wilding, D.M., Rachel L. Batterham, M.B., B.S., Ph.D., Salvatore Calanna, Ph.D., Melanie Davies, M.D., Luc F. Van Gaal, M.D., Ph.D., Ildiko Lingvay, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.C.S., Barbara M. McGowan, M.D., Ph.D., Julio Rosenstock, M.D., Marie T.D. Tran, M.D., Ph.D., Thomas A. Wadden, Ph.D., Sean Wharton, M.D., Pharm.D., Koutaro Yokote, M.D., Ph.D., Niels Zeuthen, M.Sc., and Robert F. Kushner, M.D., for the STEP 1 Study Group*

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Obesity is a global health challenge with few pharmacologic options. Whether adults with obesity can achieve weight loss with once-weekly semaglutide at a dose of 2.4 mg as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention has not been confirmed.

METHODS

In this double-blind trial, we enrolled 1961 adults with a body-mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) of 30 or greater (≥27 in persons with ≥1 weight-related coexisting condition), who did not have diabetes, and randomly assigned them, in a 2:1 ratio, to 68 weeks of treatment with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide (at a dose of 2.4 mg) or placebo, plus lifestyle intervention. The coprimary end points were the percentage change in body weight and weight reduction of at least 5%. The primary estimand (a precise description of the treatment effect reflecting the objective of the clinical trial) assessed effects regardless of treatment discontinuation or rescue interventions.

RESULTS

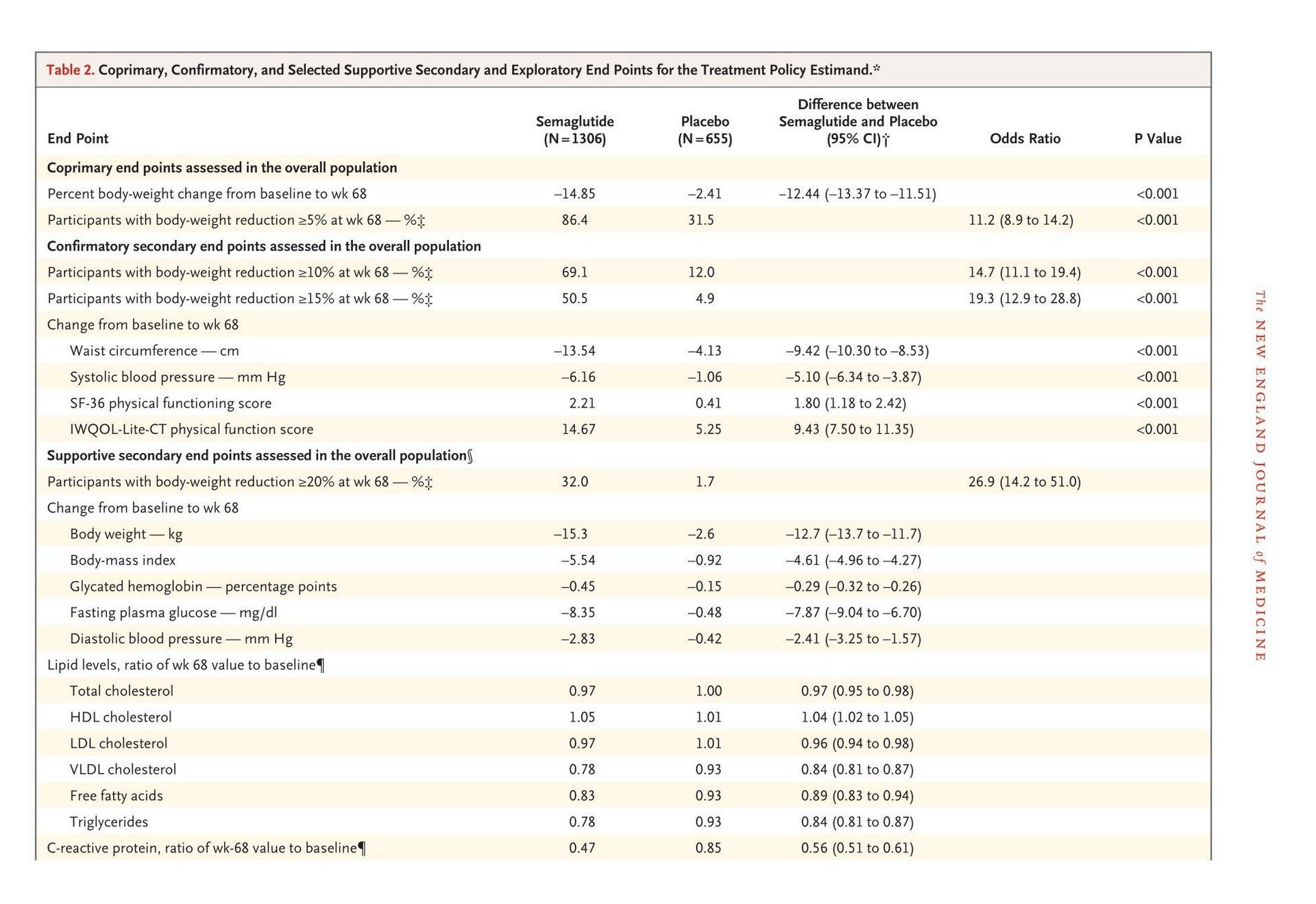

The mean change in body weight from baseline to week 68 was −14.9% in the semaglutide group as compared with −2.4% with placebo, for an estimated treatment difference of −12.4 percentage points (95% confidence interval [CI], −13.4 to −11.5; P<0.001). More participants in the semaglutide group than in the placebo group achieved weight reductions of 5% or more (1047 participants [86.4%] vs. 182 [31.5%]), 10% or more (838 [69.1%] vs. 69 [12.0%]), and 15% or more (612 [50.5%] vs. 28 [4.9%]) at week 68 (P<0.001 for all three comparisons of odds). The change in body weight from baseline to week 68 was −15.3 kg in the semaglutide group as compared with −2.6 kg in the placebo group (estimated treatment difference, −12.7 kg; 95% CI, −13.7 to −11.7). Participants who received semaglutide had a greater improvement with respect to cardiometabolic risk factors and a greater increase in participant-reported physical functioning from baseline than those who received placebo. Nausea and diarrhea were the most common adverse events with semaglutide; they were typically transient and mild-to-moderate in severity and subsided with time. More participants in the semaglutide group than in the placebo group discontinued treatment owing to gastrointestinal events (59 [4.5%] vs. 5 [0.8%]).

CONCLUSIONS

In participants with overweight or obesity, 2.4 mg of semaglutide once weekly plus lifestyle intervention was associated with sustained, clinically relevant reduction in body weight. (Funded by Novo Nordisk; STEP 1 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03548935)

The new england journal o f medicine

Obesity is a chronic disease and global public health challenge.1-3 Obesity can lead to insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,4 is associated with complications such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,2,5 and reduces life expectancy.6 More recently, obesity has been linked to increased numbers of hospitalizations, the need for mechanical ventilation, and death in persons with coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19).7,8 Although lifestyle intervention (diet and exercise) represents the cornerstone of weight management,1,2 sustaining weight loss over the long term is challenging.9 Clinical guidelines suggest adjunctive pharmacotherapy, particularly for adults with a body-mass index (BMI, the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) of 30 or greater, or 27 or greater in persons with coexisting conditions.1,2,10 However, the use of available medications remains limited by modest efficacy, safety concerns, and cost.3 Semaglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue that is approved, at doses up to 1 mg administered subcutaneously once weekly, for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults and for reducing the risk of cardiovascular events in persons with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.11 Semaglutide induced weight loss in persons with type 2 diabetes and in adults with obesity who were participants in a phase 2 trial,12-14 findings that supported further investigation. The global phase 3 Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with Obesity (STEP) program aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of semaglutide administered subcutaneously at a dose of 2.4 mg once weekly in persons with overweight or obesity, with or without weight-related complications.15 This 68-week trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of semaglutide as compared with placebo as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention for reducing body weight and meeting other related end points in adults with overweight or obesity and without diabetes

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial at 129 sites in 16 countriesin Asia, Europe, North America, and South America. The sponsor (Novo Nordisk) designed the trial and oversaw its conduct. The design has been published previously.15 The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol (available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org) was approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each study site. Investigators were responsible for data collection, and the sponsor undertook site monitoring, data collation, and analysis. All authors had full access to study data, participated in drafting the manuscript (assisted by a sponsor-funded medical writer), approved its submission for publication, and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol.

Participants

We enrolled adults (18 years of age or older) with one or more self-reported unsuccessful dietary efforts to lose weight and either a BMI of 30 or greater or a BMI of 27 or greater with one or more treated or untreated weight-related coexisting conditions (i.e., hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, or cardiovascular disease). A subgroup of participants with a BMI of 40 or less underwent dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to assess body composition. All participants provided written informed consent. Key exclusion criteria were diabetes, a glycated hemoglobin level of 48 mmol per mole (6.5%) or greater, a history of chronic pancreatitis, acute pancreatitis within 180 days before enrollment, previous surgical obesity treatment, and use of antiobesity medication within 90 days before enrollment. A full list of the eligibility criteria is provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.

Procedures

Participants were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio, through the use of an interactive Web-based response system, to receive semaglutide at a dose of 2.4 mg administered subcutaneously once a week for 68 weeks or matching placebo, in addition to lifestyle intervention; this 68-week period was followed by a 7-week period without receipt of semaglutide or placebo or lifestyle intervention. Semaglutide, administered with a prefilled pen injector, was initiated at a dose of 0.25 mg once weekly for the first 4 weeks, with the dose increased every 4 weeks to reach the maintenance dose of 2.4 mg weekly by week 16 (lower maintenance doses were permitted if participants had unacceptable side effects with the 2.4-mg dose) (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Participants received individual counseling sessions every 4 weeks to help them adhere to a reducedcalorie diet (500-kcal deficit per day relative to the energy expenditure estimated at the time they underwent randomization) and increased physical activity (with 150 minutes per week of physical activity, such as walking, encouraged). Both diet and activity were recorded daily in a diary or by use of a smartphone application or other tools and were reviewed during counseling sessions. Participants discontinuing treatment prematurely remained in the trial.

End Points and Assessments

The coprimary end points were the percentage change in body weight from baseline to week 68 and achievement of a reduction in body weight of 5% or more from baseline to week 68. Confirmatory secondary end points (in hierarchical testing order) were achievement of a reduction in body weight of 10% or more and 15% or more by week 68 and the change from baseline to week 68 in waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, physical functioning score on the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), version 2, and physical function score on the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life–Lite Clinical Trials Version (IWQOL-Lite-CT) questionnaire. (Assessments related to end points, along with supportive secondary and exploratory end points and safety assessments, are described in the Supplementary Appendix.) Body composition (total fat, total lean body mass, and regional [abdominal] visceral fat mass) was measured in the DXA subpopulation as a supportive secondary end point. Safety assessments included the number of adverse events occurring during the on-treatment period (the time during which participants received any dose of semaglutide or placebo within the previous 49 days, with any period of temporary interruption of the regimen excluded) and serious adverse events occurring between baseline and week 75. An independent external event adjudication committee reviewed selected adverse events (cardiovascular events and acute pancreatitis) and deaths. All standard assays were performed in a central laboratory.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of 1950 participants provided an effective power of 99% for the coprimary and confirmatory secondary end points, tested in a prespecified hierarchical order. Efficacy end points were analyzed in the full analysis population (all randomly assigned participants according to the intention-to-treat principle); safety end points were analyzed in the safety analysis population (all randomly assigned participants exposed to at least one dose of semaglutide or placebo). Observation periods included the in-trial period (the time from random assignment to last contact with a trial site, regardless of treatment discontinuation or rescue intervention) and the on-treatment period. All results from statistical analyses were accompanied by a two-sided 95% confidence interval and corresponding P values (with significance defined as P<0.05). Supportive secondary end-point analyses were not controlled for multiple comparisons and should not be used to infer definitive treatment effects. Two estimands — the treatment policy estimand (traditional intention-to-treat analysis, with effects assessed regardless of treatment discontinuation or rescue intervention) and the trial product estimand (effects assessed if the drug or placebo was taken as intended) — were used to assess treatment efficacy from different perspectives and accounted for intercurrent events and missing data differently, as described previously.16 All analyses in the statistical hierarchy were based on the primary treatment policy estimand (details on analysis methods are provided in the Supplementary Appendix). All reported results are for the treatment policy estimand, unless stated otherwise.

Results

Study Participants

From June through November 2018, a total of 1961 participants were randomly assigned to receive semaglutide (1306 participants) or placebo (655 participants). Overall, 94.3% of the participants completed the trial, 91.2% had a bodyweight assessment at week 68, and 81.1% adhered to treatment (Fig. S2). Rescue interventions were received by 7 participants in the semaglutide group (2 had bariatric surgery and 5 received other antiobesity medication) and by 13 in the placebo

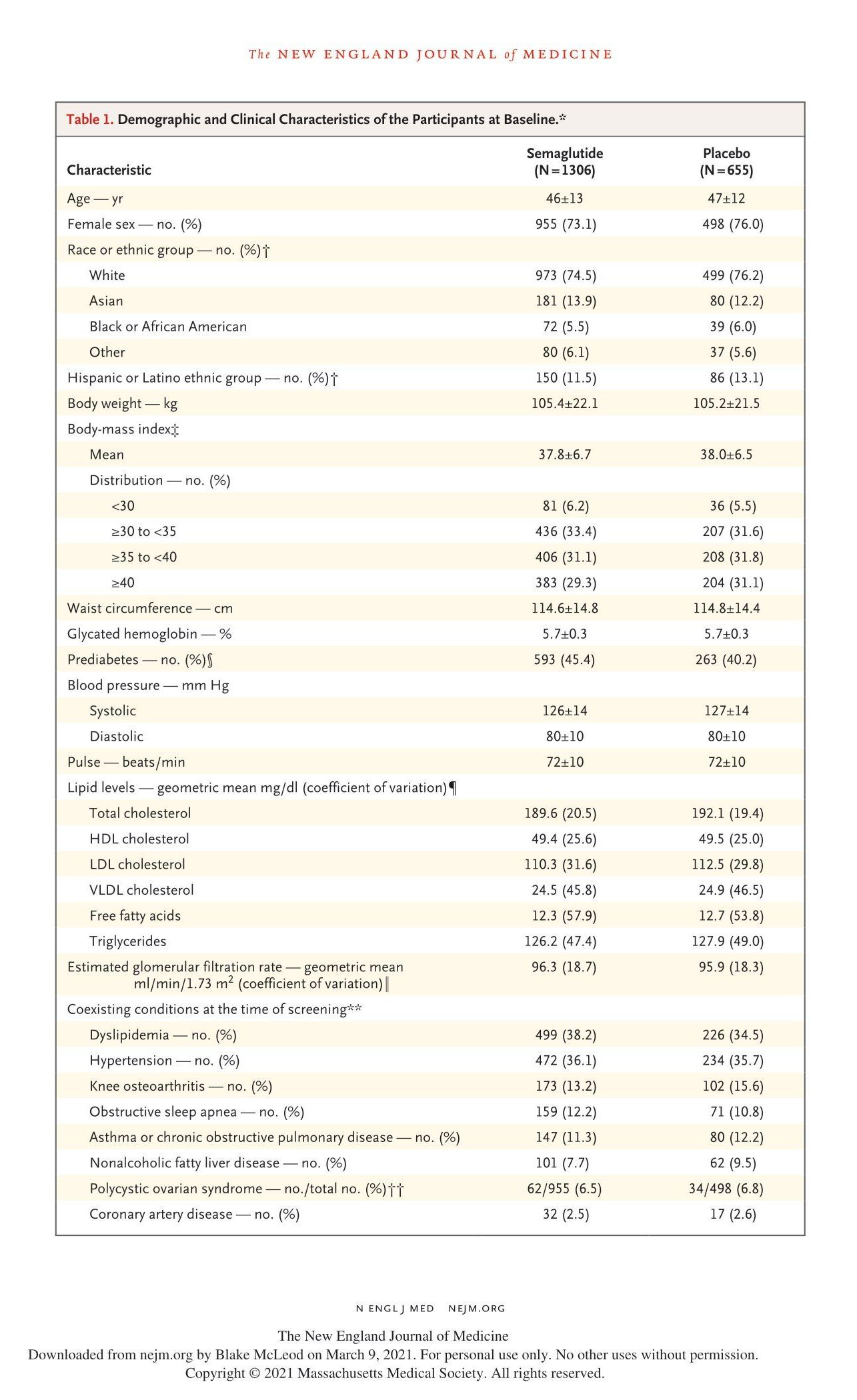

* Plus–minus values are means ±SD. HDL denotes high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, and VLDL very-low-density lipoprotein.

† Race and ethnic group were reported by the investigator. The category of “other” includes Native American, Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, any other ethnic group, and “not applicable,” the last of which is the way race or ethnic group was recorded in France.

‡ The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

§ The presence of prediabetes was determined by investigators on the basis of available information (e.g., medical records, concomitant medication, and blood glucose variables) and in accordance with American Diabetes Association criteria.17

¶ Baseline lipid levels were reported for 1281 to 1301 participants per variable in the semaglutide group, and 645 to 649 participants per variable in the placebo group. The coefficient of variation is expressed as a percentage.

‖ The coefficient of variation is expressed as a percentage.

** A coexisting condition was a history of any of the following conditions, as reported at screening: dyslipidemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnea, impaired glucose metabolism, reproductive system disorders, liver disease, kidney disease, osteoarthritis, gout, or asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

†† Data on polycystic ovarian syndrome include only female participants.

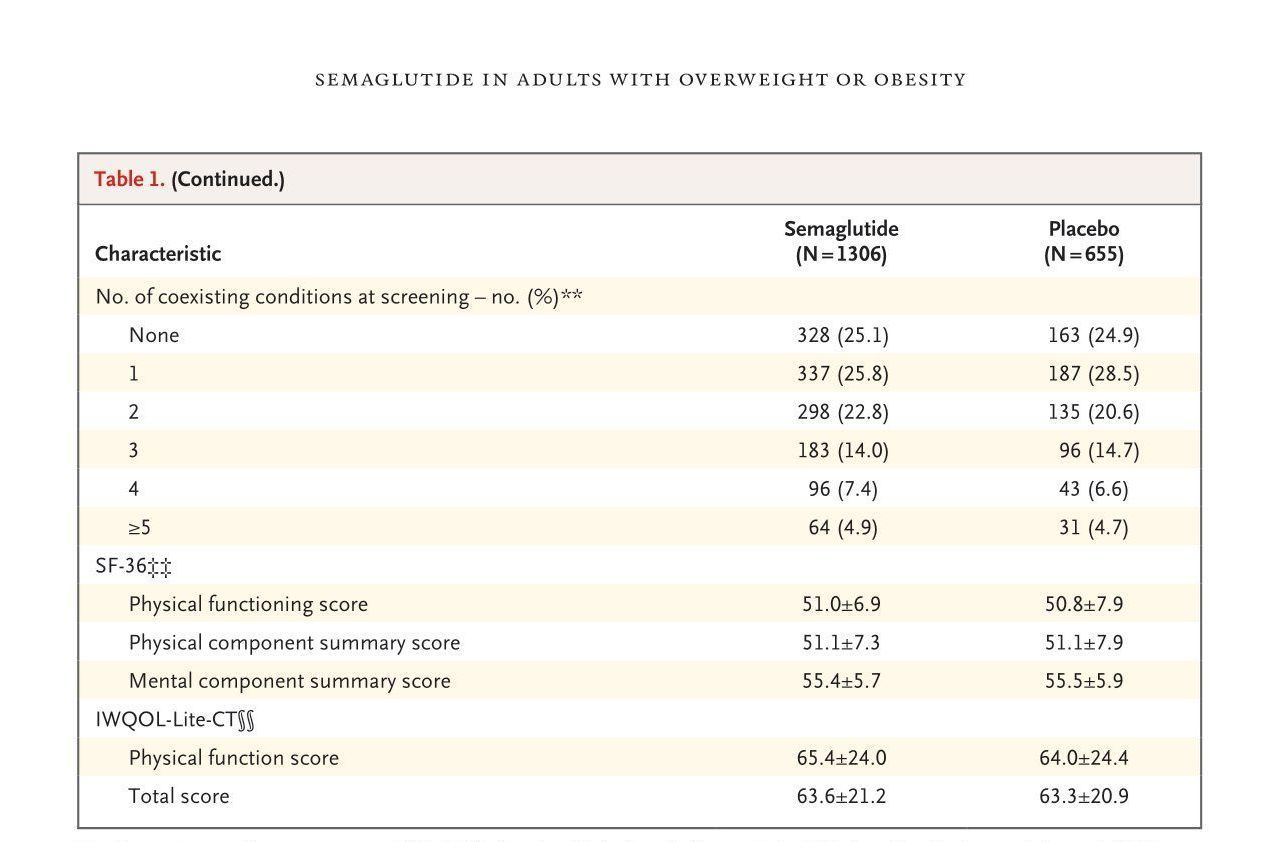

‡‡ Scores on the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) are norm-based, transformed to a scale on which the 2009 general population of the United States has a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation of 10; higher scores indicate better quality of life. Baseline scores are reported for 1296 participants in the semaglutide group and 650 participants in the placebo group.

§§ Baseline scores on the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life–Lite Clinical Trials Version (IWQOL-Lite-CT; scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better patient functioning) are reported for 1296 participants in the semaglutide group and 649 participants in the placebo group.

group (3 had bariatric surgery and 10 received other antiobesity medication). Demographics and baseline characteristics were similar in the two treatment groups (Table 1). Most participants were female (74.1%) and White (75.1%), with a mean age of 46 years. The mean body weight was 105.3 kg, the mean BMI 37.9, and the mean waist circumference 114.7 cm; 43.7% had prediabetes. At screening, most participants (75.0%) had at least one coexisting condition. The baseline characteristics of the DXA subpopulation are provided in Table S1.

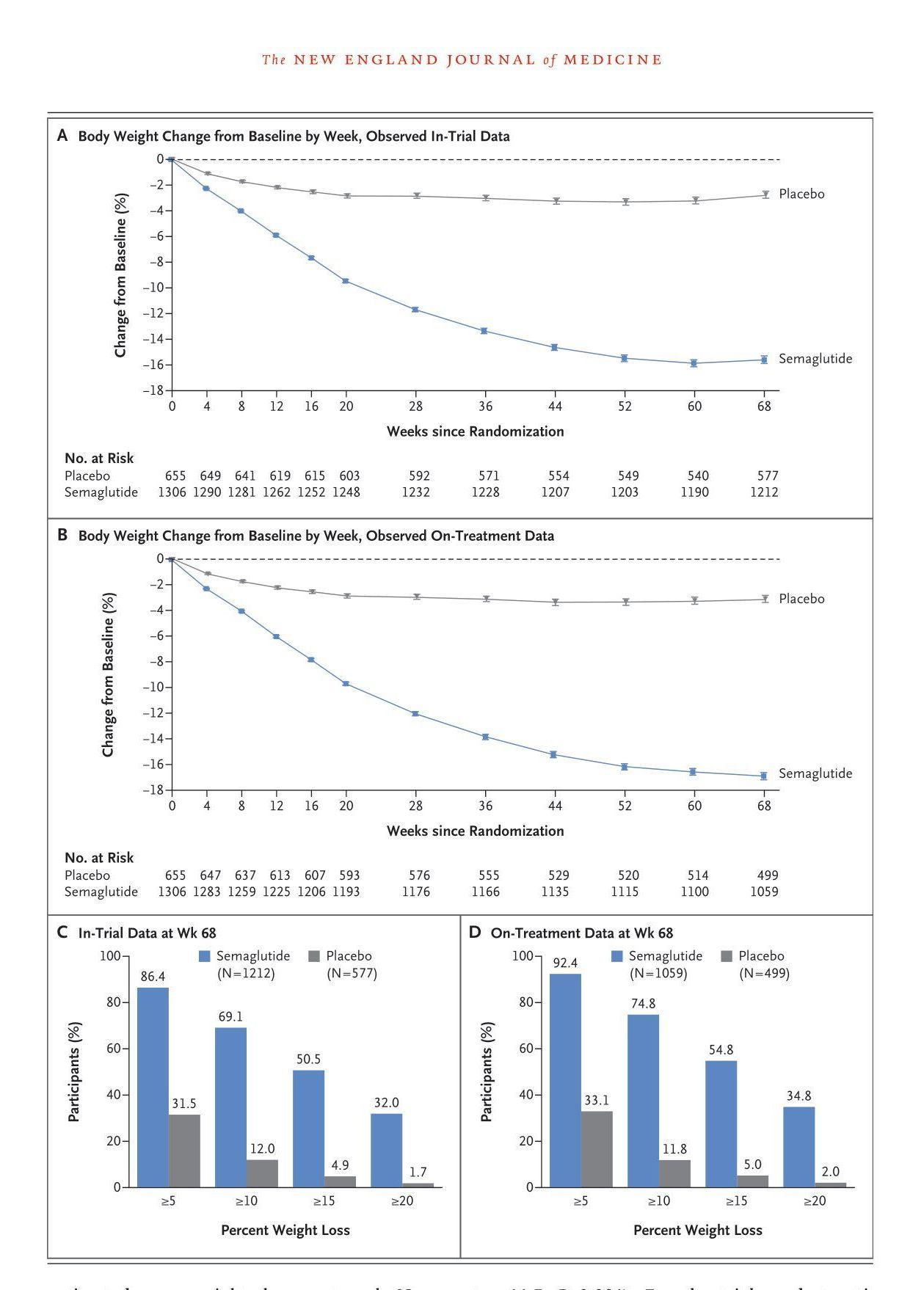

Figure 1 (facing page). Effect of Once-Weekly Semaglutide,as Compared with Placebo, on Body Weight. Panels A and B show the observed mean percentage change from baseline in body weight over time among participants in the full analysis population during the in-trial observation period (the time from random assignment to last contact with a trial site, regardless of treatment discontinuation or rescue intervention) and during the on-treatment observation period (the time

during which participants received semaglutide or placebo within the previous 2 weeks, with any period of temporary interruption of a regimen excluded). I bars

indicate standard errors. The numbers at risk are the numbers of participants with available data contributing to the means at each visit. Panels C and D show the

observed percentages of participants who had bodyweight reductions of at least 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% from baseline to week 68 during the in-trial observation

period and on-treatment observation period. Percentages were based on the number of participants for whom data were available at the week 68 visit — 1212 participants in the semaglutide group and 577 in the placebo group during the in-trial observation period and 1059 participants in the semaglutide group and 499 in the placebo group during the on-treatment observation period.

Change in Body Weight

In the semaglutide group, weight loss was observed from the first postrandomization assessment (week 4) onward, reaching a nadir at week 60 (Fig. 1A and 1B). For the treatment policy estimand (showing the effect regardless of treatment discontinuation or rescue intervention), the estimated mean weight change at week 68 was −14.9% with 2.4-mg semaglutide, as compared with −2.4% with placebo (estimated treatment difference, −12.4 percentage points; 95% CI, −13.4 to −11.5; P<0.001). For the trial product estimand (showing the effect if the drug or placebo was taken as intended), the corresponding changes were −16.9% and −2.4% (estimated treatment difference, −14.4 percentage points; 95% CI, −15.3 to −13.5). Participants who received semaglutide were more likely to lose 5% or more, 10% or more, 15% or more, and 20% or more of baseline body weight at week 68 than those who received placebo (P<0.001 for the 5%, 10%, and 15% thresholds; the 20% threshold was not part of the statistical testing hierarchy) (Table 2, Fig. 1C and 1D, and Table S2). Among the participants for whom data were available at the week 68 visit (1212 participants in the semaglutide group and 577 in the placebo group), these thresholds were reached by 86.4% (1047 participants), 69.1% (838 participants), 50.5% (612 participants), and 32.0% (388 participants), respectively, in the semaglutide group, as compared with 31.5% (182 participants), 12.0% (69 participants), 4.9% (28 participants), and 1.7% (10 participants) in the placebo group (Fig. 1C, with on-treatment data shown in Fig. 1D and the cumulative distribution of change from baseline shown in Fig. S3). The change in body weight from baseline to week 68 was −15.3 kg in the semaglutide group as compared with −2.6 kg in the placebo group (estimated treatment difference, −12.7 kg; 95% CI, −13.7 to −11.7) (Fig. S4). Data on change in body weight and achieved reduction in body weight of 5% or more (coprimary end points) as well as confirmatory and selected supportive secondary end points for the trial product estimand are provided in Table S2.

Other Confirmatory and Supportive Secondary End Points

Semaglutide was associated with greater reductions from baseline than placebo in waist circumference (–13.54 cm with semaglutide vs. –4.13 cm with placebo; estimated treatment difference, –9.42 cm; 95% CI, –10.30 to –8.53), BMI (–5.54 with semaglutide vs. –0.92 with placebo; estimated treatment difference, –4.61; 95% CI, –4.96 to –4.27), and systolic and diastolic blood pressure at week 68 (Table 2, Table S2, and Figs. S5 and S6). Benefits favoring semaglutide were also noted with respect to changes in glycated hemoglobin, fasting plasma glucose, C-reactive protein, and fasting lipid levels (Table 2).

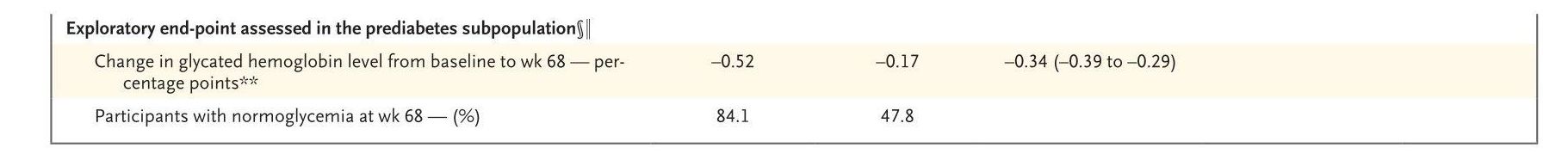

Exploratory End Points

Among participants with prediabetes at baseline, semaglutide was associated with improvements in glycated hemoglobin levels at week 68, and 84.1% of participants in the semaglutide group who had prediabetes at baseline, as compared with 47.8% of participants in the placebo group with prediabetes at baseline, reverted to normoglycemia. Results for these and other selected exploratory end points are presented in Table 2 and Table S3.

Physical Functioning and Other Participant-Reported Outcomes

SF-36 physical functioning scores (with possible norm-based scores ranging from 19.03 to 57.60) improved significantly more with semaglutide than with placebo at week 68 (P<0.001), and both SF-36 physical and mental component summary scores favored semaglutide (Table 2, Table S2, and Fig. S7). IWQOL-Lite-CT physical function scores improved significantly more with semaglutide than with placebo at week 68 (P<0.001) (Table 2 and Table S2), and there were favorable effects over placebo on IWQOL-Lite-CT total scores. The results of SF-36 and IWQOL-Lite-CT assessments showed that participants were more likely to have clinically meaningful within-person improvements in physical functioning with semaglutide than with placebo (Table S4).

Change in Body Composition

In the DXA subpopulation (140 participants), total fat mass and regional visceral fat mass were re - duced from baseline with semaglutide (Table S5). Although total lean body mass decreased in ab - solute terms (kg), the proportion of lean body mass relative to total body mass increased with semaglutide.

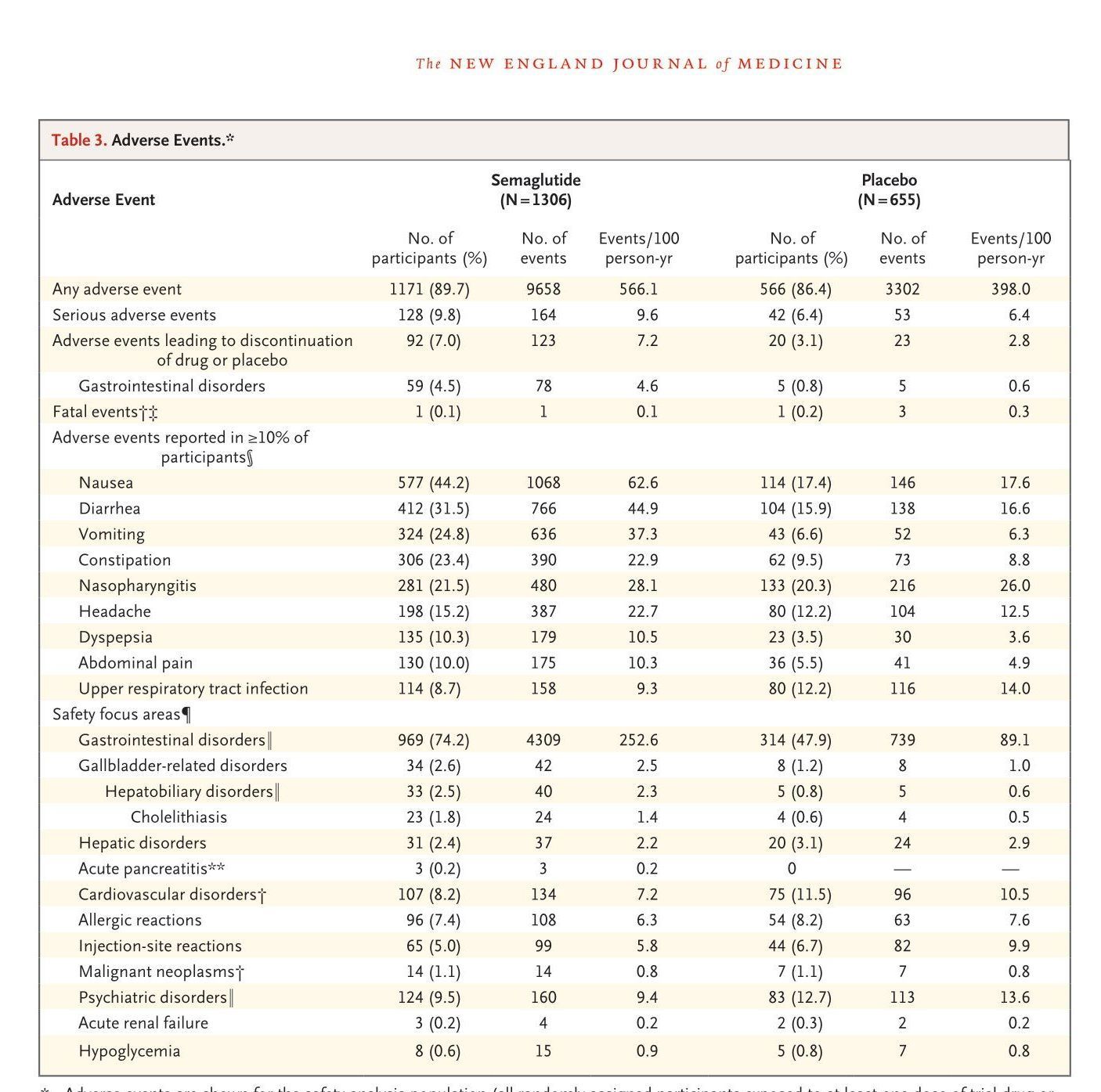

Safety and Side-Effect

Profile Similar percentages of participants in the sema - glutide and placebo groups reported adverse events (89.7% and 86.4%, respectively) (Table 3). Gastro - intestinal disorders (typically nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and constipation) were the most fre - quently reported events and occurred in more participants receiving semaglutide than those receiving placebo (74.2% vs. 47.9%). Most gastro - intestinal events were mild-to-moderate in sever - ity, were transient, and resolved without perma - nent discontinuation of the regimen (Fig. S8). Serious adverse events were reported in 9.8% and 6.4% of semaglutide and placebo partici - pants, respectively (Table 3), with the difference due primarily to a difference between the groups in the incidence of serious gastrointestinal dis - orders (1.4% of participants in the semaglutide group and 0% in the placebo group) and hepa - tobiliary disorders (1.3% with semaglutide and 0.2% with placebo). More participants in the semaglutide group than in the placebo group (7.0% vs. 3.1%) discontinued treatment owing to adverse events (mainly gastrointestinal events) (Table 3 and Fig. S9). One death was reported in each group, with neither considered by the inde - pendent external event adjudication committee to be related to receipt of semaglutide or placebo (Table 3). Gallbladder-related disorders (mostly choleli - thiasis) were reported in 2.6% and 1.2% of par - ticipants in the semaglutide and placebo groups, respectively. Mild acute pancreatitis (according to the Atlanta classification18) was reported in three participants in the semaglutide group (one participant had a history of acute pancreatitis, and the other two participants had both gall - stones and pancreatitis); all recovered during the trial period. There was no difference between groups in the incidence of benign and malignant neoplasms. Additional safety variables are de - scribed in Table 3 and Table S6.

* Adverse events are shown for the safety analysis population (all randomly assigned participants exposed to at least one dose of trial drug or placebo); since all participants received at least one dose of drug or placebo, the safety population is the same as the full-analysis population. Included are all adverse events that occurred during the on-treatment period (i.e., the period during which any dose of semaglutide or placebo was administered within the previous 49 days, with any period of temporary interruption of a regimen excluded), unless indicated otherwise. Adverse events were classified by severity as mild (causing minimal discomfort and not interfering with everyday activities), moderate (causing sufficient discomfort to interfere with normal everyday activities), or severe (preventing normal everyday activities).

† Included are events that were observed during the in-trial period (the time from random assignment to last contact with a trial site, regardless of treatment discontinuation or rescue intervention).

‡ In the semaglutide group, sudden cardiac death occurred in one participant with a medical history of hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea who had discontinued semaglutide. In the placebo group, death due to glioblastoma, aspiration pneumonia, and severe sepsis occurred in one participant each who had discontinued placebo.

§ Shown are the most common adverse events, according to the preferred term in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 22.1, reported in 10% or more of participants in either treatment group.

¶ On the basis of therapeutic experience with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and regulatory feedback and requirements, a number of safety focus areas were prespecified as being of special interest in the safety evaluation. Identified through searches of MedDRA, these preferred terms were judged to be relevant for each of the safety focus areas.

‖ This is a system organ class. (For gallbladder-related disorders, hepatobiliary disorders is the system organ class and cholelithiasis is the preferred term.)

** Acute pancreatitis was confirmed by the event adjudication committee.

Discussion

In this trial, we found that adults with obesity (or overweight with one or more weight-related coexisting conditions) and without diabetes had a mean weight loss of 14.9% from baseline with semaglutide as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention. This loss exceeded that with placebo plus lifestyle intervention by 12.4 percentage points. The 14.9% mean weight loss that we observed in the semaglutide group is substantially greater than the weight loss of 4.0 to 10.9% from baseline with approved antiobesity medications.3,19 Moreover, 86% of participants who received semaglutide, as compared with 32% of those who received placebo, lost 5% or more of baseline body weight, a widely used criterion of clinically meaningful response.2,3,20,21 Weight loss with semaglutide stems from a reduction in energy intake owing to decreased appetite, which is thought to result from direct and indirect effects on the brain.22-25 Weight loss with semaglutide was accompanied by greater improvements than placebo with respect to cardiometabolic risk factors, including reductions in waist circumference, blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin levels, and lipid levels; a greater decrease from baseline in C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation; and a greater proportion of participants with normoglycemia. Semaglutide also improved physical functioning, as assessed by SF-36 and IWQOLLite-CT, a finding that is notable given that overweight and obesity significantly impair healthrelated quality of life.26 Statistical superiority of semaglutide over placebo was achieved for all end points in the hierarchical testing procedure.

Weight loss of 10 to 15% (or more) is recommended in people with many complications of overweight and obesity (e.g., prediabetes, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea).1,20,21,27 In the semaglutide group, approximately 70% of participants achieved a weight loss of at least 10%, and approximately 50% achieved a weight loss of at least 15%. Furthermore, one third of participants treated with semaglutide lost at least 20% of baseline weight, a reduction approaching that reported 1 to 3 years after bariatric surgery, particularly sleeve gastrectomy (approximately 20 to 30% weight loss).28-31 The magnitude of reduction in cardiometabolic risk is assumed to be proportional to the amount of weight lost with both approaches (i.e., pharmacotherapy or surgery).32

Analyses from the DXA substudy suggested that semaglutide led to greater reduction in fat mass than lean body mass, a finding consistent with previous findings with semaglutide (at a dose of 1.0 mg) in persons with obesity22 and in those with type 2 diabetes.33 The weight loss and improvements with respect to cardiometabolic risk factors with semaglutide reported here will be complemented by an ongoing cardiovascular outcomes trial in participants with overweight or obesity and established cardiovascular disease (the SELECT trial; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03574597).

Liraglutide administered subcutaneously once daily is the only GLP-1 receptor agonist approved for weight management.3,19,34 Our trial showed greater mean placebo-corrected weight reductions with once-weekly 2.4-mg semaglutide plus lifestyle intervention (12.4%) than those reported with once-daily 3.0-mg liraglutide plus lifestyle intervention in the 56-week SCALE (Satiety and Clinical Adiposity — Liraglutide Evidence in Nondiabetic and Diabetic Individuals Obesity and Prediabetes) trial (4.5%).34,35 In addition, the weightloss phase with semaglutide persisted longer than that reported with liraglutide35 and did not reach the nadir until week 60. However, these two studies differed in their participant population, which limits the robustness of between-study comparisons.

At week 68, 31% of participants who received placebo had lost at least 5% of baseline body weight, with 12% and 5% having achieved reductions of at least 10% and at least 15%, respectively, findings that show good adherence to lifestyle interventions. Similar results were observed at week 56 in the SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes trial.35

Currently, approved antiobesity drugs require administration once, twice, or three times daily,3,19 and a once-weekly regimen may improve treatment adherence. The once-weekly 2.4-mg dose of semaglutide was chosen for the present study on the basis of pharmacokinetic modeling that suggested that the 2.4-mg weekly dose had a maximum steady-state concentration similar to a once-daily 0.4-mg dose investigated in a phase 2 dose-finding trial in participants with obesity.14 The results of our study with once-weekly semaglutide at a 2.4-mg dose are consistent with the results of the phase 2 study, which showed an 11.6% greater reduction in body weight with once-daily semaglutide at a dose of 0.4 mg than with placebo after 52 weeks of treatment.14

The safety of semaglutide was consistent with that reported in the phase 2 study with oncedaily dosing in participants with obesity14 and in the trials of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in persons with type 2 diabetes (involving more than 8000 participants receiving doses up to 1 mg),12 as well as with that reported for the GLP-1 receptor agonist class in general.13,36 As is typical of this drug class,13,37 transient, mild-tomoderate gastrointestinal disorders were the most frequently reported adverse events, and more participants in the semaglutide group than in the placebo group discontinued the assigned regimen after such events. Nausea was the most common gastrointestinal event, occurring primarily during the dose-escalation period, a finding similar to that reported with liraglutide at a dose of 3.0 mg.35 Gallbladder-related disorders, principally cholelithiasis, were more common in the semaglutide group, a finding consistent with previous reports for GLP-1 receptor agonists38,39 and with the known effects of rapid weight loss.40,41 The incidence of cholelithiasis with semaglutide was in line with that of liraglutide at a dose of 3.0 mg.35 No new safety concerns arose.

Strengths of this trial included the large sample size and high rates of adherence to the treatment regimen and completion of the trial. Limitations included the preponderance of women and White participants, the relatively short duration of the trial, the exclusion of persons with type 2 diabetes, and the potential that participants who were enrolled may represent a subgroup with greater commitment to weight-loss efforts than the general population. Although the DXA data we report provide greater insight into the weight-loss effects of semaglutide, such assessments were performed in only a subpopulation of participants.

Our trial showed that among adults with overweight or obesity (without diabetes), onceweekly subcutaneous semaglutide plus lifestyle intervention was associated with substantial, sustained, clinically relevant mean weight loss of 14.9%, with 86% of participants attaining at least 5% weight loss.

Supported by Novo Nordisk. Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

We thank the trial participants and the trial site staff; Lisa von Huth Smith of Novo Nordisk, Denmark, for support with data presentation of participant-reported outcomes and critical review of an earlier draft of the manuscript; and Paul Barlass of Axis, a division of Spirit Medical Communications Group, for medical writing and editorial assistance with an earlier draft of the manuscript (funded by Novo Nordisk).

Appendix

The authors’ affiliations are as follows: the Department of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, Institute of Life Course and Medical Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool (J.P.H.W.), University College London Centre for Obesity Research, Division of Medicine, University College London (R.L.B.), the National Institute of Health Research, UCLH Biomedical Research Centre (R.L.B.), the Centre for Weight Management and Metabolic Surgery, University College London Hospital (R.L.B.), and the Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (B.M.M.), London, and the Diabetes Research Centre, University of Leicester (M.D.) and the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (M.D.), Leicester — all in the United Kingdom; Novo Nordisk, Søborg, Denmark (S.C., M.T.D.T., N.Z.); the Department of Endocrinology, Diabetology, and Metabolism, Antwerp University Hospital, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium (L.F.V.G.); the Departments of Internal Medicine/Endocrinology and Population and Data Sciences, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (I.L.), and the Dallas Diabetes Research Center at Medical City (J.R.) — both in Dallas; the Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (T.A.W.); York University, McMaster University and Wharton Weight Management Clinic, Toronto (S.W.); the Department of Endocrinology, Hematology, and Gerontology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University and Department of Diabetes, Metabolism, and Endocrinology, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan (K.Y.); and the Division of Endocrinology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago (R.F.K.).

References

1. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract 2016; 22:Suppl 3:1-203.

2. Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, et al. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes Facts 2015;8:402-24.

3. Bessesen DH, Van Gaal LF. Progress and challenges in anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6:237-48.

4. Neeland IJ, Poirier P, Després J-P. Cardiovascular and metabolic heterogeneity of obesity: clinical challenges and implications for management. Circulation 2018; 137:1391-406.

5. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2009;9:88.

6. Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 2009;373:1083-96.

7. Yang J, Hu J, Zhu C. Obesity aggravates COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2020 June 30 (Epub ahead of print).

8. Sanchis-Gomar F, Lavie CJ, Mehra MR, Henry BM, Lippi G. Obesity and outcomes in COVID-19: when an epidemic and pandemic collide. Mayo Clin Proc 2020;95:1445-53.

9. Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1597-604.

10. Wharton S, Lau DCW, Vallis M, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 2020;192:E875-E891.

11. Food and Drug Administration. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection prescribing information, revised. 2020 (https:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda _docs/label/2020/209637s003lbl.pdf).

12. Aroda VR, Ahmann A, Cariou B, et al. Comparative efficacy, safety, and cardiovascular outcomes with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: insights from the SUSTAIN 1-7 trials. Diabetes Metab 2019; 45:409-18.

13. Nauck MA, Meier JJ. Management of endocrine disease: are all GLP-1 agonists equal in the treatment of type 2 diabetes? Eur J Endocrinol 2019;181:R211-R234.

14. O’Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B, et al. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide compared with liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;392:637-49.

15. Kushner RF, Calanna S, Davies M, et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg for the treatment of obesity: key elements of the STEP trials 1 to 5. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28: 1050-61.

16. Wharton S, Astrup A, Endahl L, et al. Estimating and interpreting treatment effects in clinical trials for weight management: implications of estimands, intercurrent events and missing data. Int J Obes (in press).

17. American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017;40:Suppl 1:S11-S24.

18. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis — 2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013;62:102-11.

19. American Diabetes Association. 8. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes — 2020. Diabetes Care 2020; 43:Suppl 1:S89-S97.

20. Williamson DA, Bray GA, Ryan DH. Is 5% weight loss a satisfactory criterion to define clinically significant weight loss? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:2319-20.

21. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab 2016;23: 591-601.

22. Blundell J, Finlayson G, Axelsen M, et al. Effects of once-weekly semaglutide on appetite, energy intake, control of eating, food preference and body weight in subjects with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017;19:1242-51.

23. Gabery S, Salinas CG, Paulsen SJ, et al. Semaglutide lowers body weight in rodents via distributed neural pathways. JCI Insight 2020;5(6):e133429.

24. Knudsen LB, Lau J. The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019; 10:155.

25. Friedrichsen M, Breitschaft A, Tadayon S, Wizert A, Skovgaard D. The effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly on energy intake, appetite, control of eating, and gastric emptying in adults with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020 December 2 (Epub ahead of print).

26. Kolotkin RL, Andersen JR. A systematic review of reviews: exploring the relationship between obesity, weight loss and health-related quality of life. Clin Obes 2017;7:273-89.

27. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1481-6.

28. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes — 3-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2002-13.

29. Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. Bariatric surgery and longterm durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg 2016;151:1046-55.

30. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial — a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2013;273:219-34.

31. Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA 2013;310:2416-25.

32. Benraouane F, Litwin SE. Reductions in cardiovascular risk after bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Cardiol 2011;26:555-61.

33. McCrimmon RJ, Catarig A-M, Frias JP, et al. Effects of once-weekly semaglutide vs once-daily canagliflozin on body composition in type 2 diabetes: a substudy of the SUSTAIN 8 randomised controlled clinical trial. Diabetologia 2020;63:473- 85.

34. Food and Drug Administration. Saxenda (liraglutide) injection prescribing information, revised. 2020 (https://www .accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/ label/2020/206321s011lbl.pdf).

35. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med 2015;373:11-22.

36. Lyseng-Williamson KA. Glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor analogues in type 2 diabetes: their use and differential features. Clin Drug Investig 2019;39:805-19.

37. Bettge K, Kahle M, Abd El Aziz MS, Meier JJ, Nauck MA. Occurrence of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea reported as adverse events in clinical trials studying glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a systematic analysis of published clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017; 19:336-47.

38. Faillie J-L, Yu OH, Yin H, HillaireBuys D, Barkun A, Azoulay L. Association of bile duct and gallbladder diseases with the use of incretin-based drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1474-81.

39. Nauck MA, Muus Ghorbani ML, Kreiner E, Saevereid HA, Buse JB. Effects of liraglutide compared with placebo on events of acute gallbladder or biliary disease in patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events in the LEADER randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1912-20.

40. Erlinger S. Gallstones in obesity and weight loss. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;12:1347-52.

41. Quesada BM, Kohan G, Roff HE, Canullán CM, Chiappetta Porras LT. Management of gallstones and gallbladder disease in patients undergoing gastric bypass. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16: 20